Donors conducting orchestras full of paid pipers

All journalists treasure their independence, and can be wary, even borderline paranoid, about the influence the moneymen have over their work. In truth though, influence and independence are tricky metrics to measure.

Historically the press shares power and responsibility over a ragged line between reporters’ independence and proprietors’ influence, indirectly applied. “There are many ways in which you can influence a newspaper without giving a downright instruction,” Andrew Neill, eleven years editor of the London Sunday Times for Rupert Murdoch, once told UK parliamentarians.

Many journalists thought the line-drawing was liberating, excluding them from the responsibilities of business development. Not so much now. Revenues are declining as readerships are shifting. “We’re all in the non-profit media nowadays,” quips a former Fleet Street colleague of mine. The rule dividing the business of media from the trade of journalism was a custom more honour’d in the breach than the observance, but generally it was at least well understood.

Do charitable foundations even see, let alone understand, the line between key donors and the non-profit media sector they increasingly sustain? News organisations committed to public interest and community reporting? And how to relate to the newest players on the block, the Silicon Valley billionaires willing to commit money to shutter media they dislike, as Peter Thiel did with Gawker, or cut funds to media which no longer fit a “refined” long-term business strategy, as Pierre Omidyar did with Reported.ly?

A forthcoming report, A Marriage Of Convenience – Looking At The New Donor-Journalism Relationship, aims to answer some of these questions. The fear is that the ragged line between money and medium is being blurred, and charitable donors will influence non-profit media content. Anya Schiffrin is leading the production of the report. She notes that today’s start-ups “are often staffed by a couple of people who are doing fundraising as well as writing and commissioning stories and it’s not realistic to expect these small outlets to erect big walls and structures”.

Maybe not realistic, but still necessary. Schiffrin, director of the Media & Technology Program at the School of International & Public Affairs at Columbia University, thinks it will probably be up to the donors to set up the mechanisms because they are bigger, have more influence, and thus have the capability to do so. But can they be trusted? Do they themselves understand the rules?

A British parliamentary study listed the means of influence open to an owner: “Direct interference in a story, communication to the editor of what is expected of him, appointment of an editor and team that reflect a particular world view, investment in journalism or investment in specific types of journalism”. It’s the last two, the power to grant or withdraw funds, that is giving foundations a disproportionate influence over non-profit media.

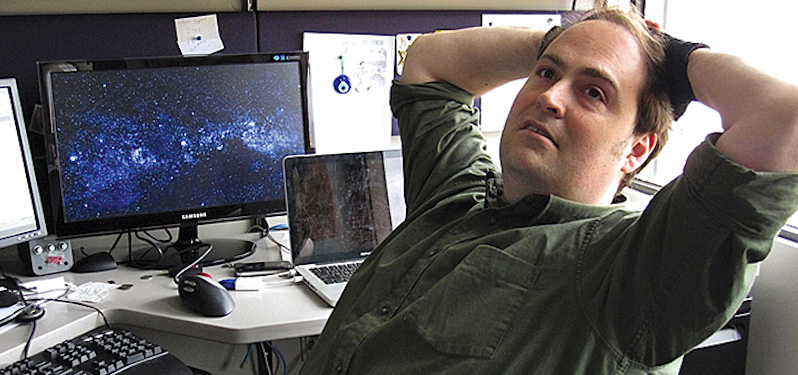

Billionaire eBay founder Pierre Omidyar was not the ‘owner’ of social news-wire project reported.ly, run by former NPR staffer Andy Carvin (main image) but he might as well have been. In August Omidyar’s company First Look Media (FLM), Carvin’s employer, cut off funding. It was a shock to Carvin, who had spent six months working with FLM staffers on a new business plan. “Everyone seemed enthusiastic about the plan,” he told Fortune magazine, “right until the last minute, when I was told that instead of expanding our funding, we were going to be defunded entirely. I was told that reported.ly didn’t fit into FLM’s overall content strategy any more, so that was that.”

Fortune reporter Mathew Ingram, a friend of Carvin, theorises that Omidiyar’s objectives simply reverted to business over philanthropy. The business side of the operation had no use for Carvin’s project, despite its extraordinary prescience and sudden timeliness. When it was first created in 2014, reported.ly was almost unique in that it had no website and ‘lived’ as a news entity inside social networks. Two years later the mainstream media is steeling itself for the difficult transition to ‘platform publishing – on Facebook, Twitter and Google. FLM is cutting loose a project that was born in this environment.

Other recipients of FLM’s qualified largesse complain about its managerial meddling and indecisiveness. Defenders of the foundation argue that the aim now is to recreate FLM as a “research lab” for journalism. Ingram has said that he preferred to see FLM’s troubles as evidence of experimentation: “not just in terms of the journalism the company is doing, but in terms of how the company itself functions as well. And sometimes experiments fail. That’s how we learn.”

Carvin is a first class journalist, and he accepts that he made a few mistakes with the business model. But that’s the problem that money people – be they stakeholders, producers, investors or donors – should focus on. Now Carvin is back where he started, one of the scores of digital start-ups that rely on foundation funding, as Schriffin reminds, run by people who are doing the fundraising as well as working as reporters.

“As donor-media relationships increase, and with it editorial influence by foundations, it’s crucial to have a thorough understanding of how this financial model affects what information societies receive.” Schiffrin highlights two particular issues that, if addressed, might help. There is a rich and diverse amount of funding for both media development and news production, but little coordination between donors. More trickily, there’s no universally-agreed upon standards of behaviour or processes to guide the application of good practice, although she notes the majority surveyed support the idea of voluntary codes of conduct for the funder-owners of the means of media production.

The other factor worth noting: the trends in non-profit fundraising are moving towards personalised relationships between key members of the charity’s staff and the major donor in person. In the US it has seen the rise of the donor-advised fund, which allows donors to make a charitable contribution, receive an immediate tax benefit and then recommend grants from the fund over time. A more ‘transactional’ form of fundraising …applied to donors who have a much higher level of involvement with the charity, such as corporate and high net worth individuals,” as one UK thinktank put it.

What’s in it for them? As former Daily Mirror editor Roy Greenslade reminded the UK parliamentary study team, there are four reasons for owning a newspaper: “Profit, propaganda, prestige and public service.” Funders like First Look Media worry about profit before content, and see little prestige in failure. But for those donors with ambitions of sharing a humanitarian message in the public service, a role in setting the content’s agenda is essential.

Marius Dragomir highlights this problem in his own review of Schiffrin’s opening text. Aid & development donor funding comes with ‘guidelines’ on what topics should be covered and ‘suggestions’ for story ideas, he writes. “Some donors give journalists tips about sources that should be included or shunned during reporting.” Without clear checks and balances in place, he warns, “donors will become totally indistinguishable from the crowd of owners and funders who use journalism to protect their friends, name and wealth.”

Dragomir worked for more than a decade with the Open Society Foundations, one of the leading funders of media development (and one frequently accused of propagandising at the expense of repressive regimes). He notes that more than a third of the donors interviewed for Schiffrin’s study said that over half of their media-related grants are meant to promote or support coverage of “designated subject areas”. The intentions may be honorable – who could argue with the ambition of the Sandler Foundation’s funding for media ready to Expose Corruption and Abuse To Produce Systemic Reform – and it may fall short of propaganda, but in some ways this reality is both predictable and defensible.

Just as private donors like Pierre Omidyar have tech development’s approach to investment hardwired into their strategies, media funding by state and institutional donors comes attached to the global aid and development agenda. “There is a market failure when it comes to the kind of journalism that can hold power to account and best support an informed society,” media development thought leader James Deane has said. “Market failures which result in negative development outcomes are what the aid system exists to solve.”

Here the “market failure” in the media sector is in the inadequate delivery of information of public interest and key to human security. It’s this that has driven funders like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to give media outlets funding for coverage of malaria eradication and a raft of other media led health issues. If Reported.ly didn’t deliver the kind of news that suited First Look’s agenda, there’s no question that the Gates’ much clearer requirements are being met more easily by its grantees.

Among many other media projects, the foundation supports the Innovation in Development Reporting Grant Programme, operated by the European Journalism Centre (EJC). Fairly typical of its kind, the programme aims to enable better coverage of international development issues in Europe, with preference given to innovative, “even experimental reporting, employing state of the art presentation methods and techniques of journalistic storytelling”.

Initiatives like these parallel changes in the focus of media development initiatives in the developing world and in crisis-hit states, led by western state aid & development agencies, notably from Sweden and the United States. Increasingly traditional efforts aimed at building sustainable media systems and institutions have had to give way to the more pressing needs of crises in the Middle East and Africa.

Where these donors have struggled has been in the incorporation of new technology into their work. Academics Indra de Lanerolle & Christopher Wilson among others, have highlighted the “failure of uptake” of this technology, digital tools declined by the very people the tools were intended to assist, demand-led initiatives without a demand. The tools are often deployed based on limited understanding of their intended users in their intended contexts.

Values are brought into question, writes Deane. “Media support initiatives are particularly vulnerable to the charge that they start with a set of assumptions of how they think things ought to work rather than how power, politics and government is in fact organised and how change can be best achieved.”

There perhaps we have it. Donors from funds grounded in the technology sector are struggling with political power relations in media. Government funders from an aid & development sector long acclimatised to politics are struggling with introducing technology . And both are perhaps no nearer to an understanding of the ethical questions that control of resources raises in the development of free and independent journalism.