Capping the polluting effects of fake news

Can we treat problems like fake news, native ads and ad-bot fraud as dangerous by-products of industrial scale content production online – just as CO2 emissions are seen as a dangerous by-product of industrial scale energy production? And act accordingly?

The metrics that reward publishers with advertising income reward quantity over quality on Facebook and Google. Advertisers used to pay magazines and papers to line up properly targeted audiences for their ads. The grand duopoly has taken over that paying task and extracts millions from it.

Ben Thompson: “Newspapers no longer have a monopoly on advertising, can never compete with the Internet when it comes to bundling content, and news remains both valuable to society and, for the same reasons, worthless economically (reaching lots of people is inversely correlated to extracting value, and facts — both real and fake ones — spread for free).”

It’s the end for those who hoped that the costs of creating new content might be at least matched by the income it generated, a online media ‘perpetual motion machine‘. But it turned out that the frictionless technology – with its zero distribution costs and zero transaction costs – that the ‘machine’ required works only for Google and Facebook, and works best of all for junk in bulk.

During the US presidential campaign news fraudsters gamed the system to flood Facebook with pro-Trump fake-news websites. “The company’s business model, algorithms and policies,” Zeynep Tufekci wrote of Facebook, “entrench echo chambers and fuel the spread of misinformation.” The market is poisoned by its own products; threatening the “information ecosystem” that sustains participatory democracy. “Information is as critical as the air we breathe,” writes Tara Susman-Peña. “Without information, people can neither understand nor effectively respond to the events that shape their world.”

All might agree that levels of such ‘pollutants’ in the media ecosystem need to be cut, but the limitations of regulation and the online sector’s deep reliance on high-earning, high-polluting content obstructs the process. Hence this thought experiment. Why not stretch the analogy a bit further and consider a system that rewards low-emitters and penalises high-emitters by a transfer of capital – as a redistributed share of ad income – from the latter to the former?

The blunt force way to manage such a transfer would be for the duopoly to penalise ‘dangerous’ online media ‘emissions’ and proportionately cut ad income remittances from high emitters. Alternatively the two could take less drastic course and take a lead from the energy sector and its Cap & Trade mechanism, a gradualist approach to balancing reduction of emissions that aims to limit its impact on profitability and market share.

Cap & Trade’s biggest exponent, the EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) covers some 11,000 power stations and industrial plants in 30 countries and aimed to reduce emissions in 2020 to 21% below their level in 2005. It sets a cap on total emissions and energy firms are assigned allowances that add up to the cap. The ETS trade in permits is worth around $150bn annually. The participating companies measure and report their emissions and hand in one allowance for each tonne they release. The allowances can be traded, rewarding low emitters, who ‘sell’ spare allowances to high polluters.

Theoretically, applying the system to online media – content providers with high ‘emission’ levels would have their allowances set in the same way, and could ‘buy’ extra allowances from low emitters. The big two could automate the whole process, and factor it into the algorithmic calculations that govern payments based on CPM and CTR data from sites and adverts.

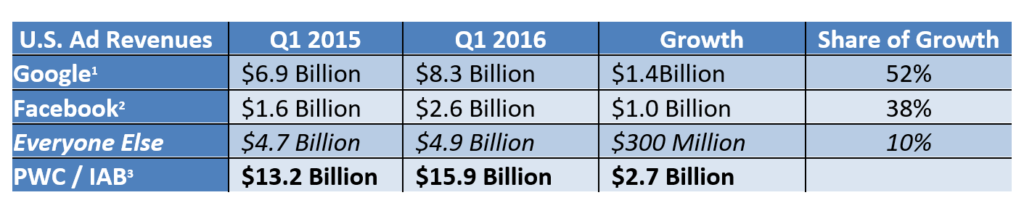

Table by Jason Kint.

Ethically it’s hard to swallow – an online media permits system that allows misrepresentation for profit. But as a industry-friendly approach to rewarding the saintly and encouraging better behaviour among sinners it might have virtue for a sector dominated by players who may be too big to regulate.

Ideally there’d be no net loss of capital in the online media sector overall – as there would be if Google & Facebook took the revenue from cap-breakers on behalf of their shareholders, or imposed excessive fees or onerous regulations on capital transfers between emitters to savers. There’s no such thing as ‘perpetual motion’ – even within the artificial laws of physics created by big search & social – but as long as capital continued flowing from emitters to savers, we’d be closer to it at least.

The system is not a simple answer to the online media sector’s problems with managing the duopoly’s market. Back in the energy sector the ETS struggles with a surplus of spare allowances as the sector tames its emissions, depressing prices – down from 29.80 euro each in July 2008 to 5.27 euro this month. Efforts to reform trading practice or tweak the market to raise unit prices are blocked by disputes between democratically accountable EU member states. That’s not an obstacle to the market autocracies of Google and Facebook.

The ETS struggles to manage the market agnostically, not preferring particular technologies or industrial practices – while the duopoly is free to apply rules that efficiently reduce its own in-house pollutant problem. There’s no shortage of over-emitters in the online media sector ready to ‘buy’ allowances from low emitters of fake news, native ads and ad-click fraud. Membership of the market could become a condition of access to its higher-value opportunities.

In an ideal world we wouldn’t need them, but the ETS and derivative carbon markets like it are a negotiated solution to the existential threat of global warming. It’s capitalism’s best offer of a means to meet that threat, while sustaining a trade on which society relies, and without fatally compromising its commercial viability or ability to maintain capital flows or innovative practice.

Applying such pragmatism to the online media market would require some basic pre-conditions. There would have to be a means of measurement. The ‘weight’ of media ‘emission’ should be the same, regardless how it is emitted, or prevented by different editorial production processes. Of course, there’s no dispute over what constitutes CO2 in the energy sector, even if there’s room for dispute about how, and how much CO2 is produced by different energy production processes. In the energy sector a ton of CO2 has to be priced the same no matter how it is emitted or prevented by the power plant’s engineers.

Yet the maths is straightforward: if a gallon of petrol weighs 6.3 pounds and you burn it, the carbon combines with oxygen and the weight of the CO2 emitted is 20 pounds. So for fairness’ sake, the Facebook & Google algorithms have to be as precise about what constitutes fake news, native ads and fake news, as the energy sector is about what constitutes CO2. Again, it’s more easily done within the closed commercial ecosystem of Facebook & Google – self-contained universes with their own rules of nature – defined and enforced by their terms & conditions of trade.

The alternative is to deal with EU and/or UK regulation. Professor Leighton Andrews, a former minister and BBC public affairs chief, is among several influential figures now arguing for an enforced levy on ad receipts to support media outlets hit by their dominance of online advertising. There also needs to be effective recognition, he says, that certain internet intermediaries or online platforms are media organisations, in Ofcom’s words, ‘editorially responsible providers’, with implications for the regulation of ‘fake news’.

This is how business works in a world with zero distribution costs and zero transaction costs, says Thompson. “Consumers are attracted to an aggregator through the delivery of a superior experience, which attracts modular suppliers, which improves the experience and thus attracts more consumers, and thus more suppliers in the aforementioned virtuous cycle.”

Publishers can become ‘modular suppliers’ to the duopoly’s aggregated markets, selling the promise of quality reporting via off-platform subscriptions to individuals. The duopoly might worry about the tide of market outrage, anti-trust action and prospective regulation rolling their way. Offering subsidies to selected media in the manner of oil companies investing in school districts in Nigeria might be useful as a kind of corporate social responsibility programme.

A future regulatory framework might require the platforms to commit to a prominent, subsidised place on their networks in the same way conventional broadcast networks can be committed to fixed levels of news and educational programming under the terms of their licences. But it would only be a small patch on the broad scale of the problem, and would still need a means of redistributing income within the system itself that would need to be open to new players and adaptable to emerging markets.

Staying with the thought experiment, I’d speculate that in the long run, establishing a derivatives market would redefine the relationship between different media creators, and their collective and individual relationships with the duopoly via which it trades. Such a redefinition would begin a managed negotiation between interests, covering the nature of good and bad content, preserving capital flow into and around the media economy, while allowing proactive intervention to prevent lasting damage to the ecosystem’s key constituents, providers of validated, sourced information.

And as long as I’m extrapolating on an industrial scale, it might eventually allow the development of a framework that allows media companies to ride the duopoly’s data & trade infrastructure, broadly speaking, in the same way private trains ride independent rail networks. Not necessarily well, speaking as a Southern Railways customer, but in an accountable, commercial relationship that is bound by terms and conditions with fines for breached standards.

Such a relationship would open up gateways where threats to privacy rights and imbalances in the attention economy could be monitored as data moved through them. These gateways might be a more manageable space for the kind of public regulator needed to succeed agencies like OFCOM, founded years before the introduction of the smartphone and the rise of Big Search & Social.